Have you ever wondered how vector allows you to insert new elements without worrying about running out of space? Do you know that vector is basically an array? Why is vector using iterator? This article will clear those questions for you!

Bjarne Stroustrup - ISO CPPAnd, yes, my recomendation is to use by default.

#Introduction

Vector is the C++ Standard Template Library (STL) container that stores a collection of objects. Just like C-arrays, vector supports Random (Direct) Access and pointer-arithmetic operations. Unlike C-arrays, vectors support many other functionalities to make your day easier:

- Dynamic reallocation (this is our focus)

- Templated

- Iterators

- Memory management

- Functions to add, remove, modify and retrieve information.

Our focus in this article is dynamic reallocation. Basically, when a vector is about to run out of space for new elements, it will allocate a new space with a sufficient size, then copy the old elements from the original space to the new one. But how does it work? What are the necessary member fields to accomplish it? How does the dynamic reallocation mechanism under the programming perspective?

This article does not show the actual implementation of std::vector.

The implementation is complex due to many support for different scenarios

and use cases. My focus is more likely on the design and hopefully, you can

come up with your own implementation from there.

#Member fields

As mentioned above, STD vector acts exactly like traditional C-arrays. So, using an array internally would be a good idea. As it turns out, STD vector actually uses an internal C-array to store data. The C-array is dynamically allocated on the heap, which can be done over malloc(), operator new, or std::allocator.

Before revealing what the member fields look like, there are some concerns that we need to address due to dynamic memory allocation:

- We want to know where the allocated space starts and ends. Missing them can lead to a memory leak.

- We want to know how many elements there are. Missing it can cause a severe overflow.

Dynamically-allocated memory operations always a pointer pointing to the first block. So we already know where it starts. Then, how do we keep track of how many elements and where does this array end?

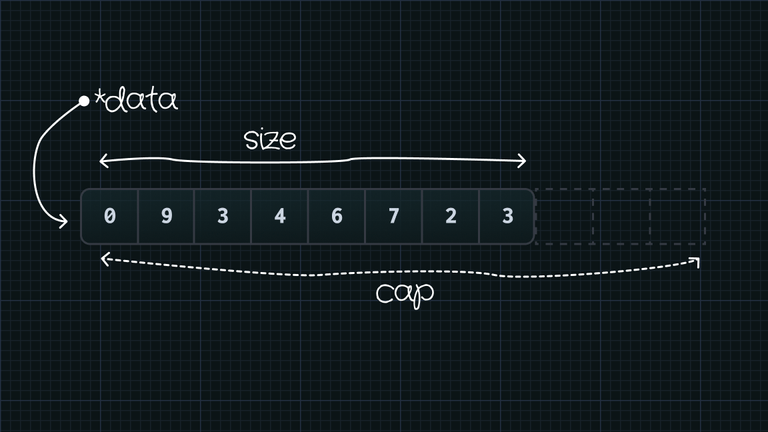

A straight-forward solution is to have two member fields to the keep track of them. Let's name them size for the number of elements, and cap for the capacity of this array. Then we can just do pointer-arithmetic operations to work with them

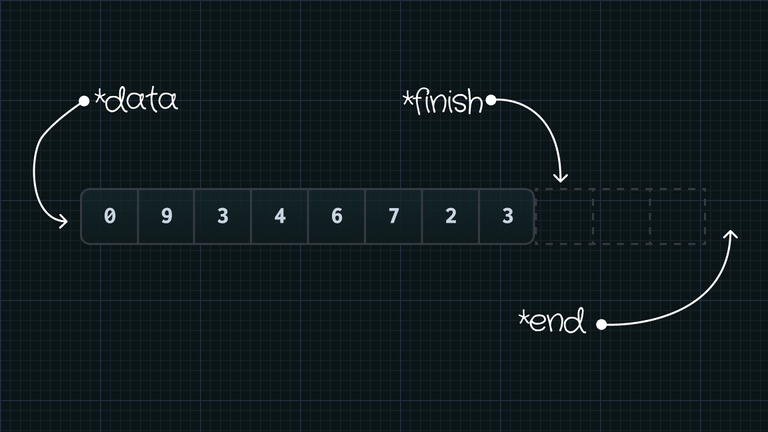

class vector{ public: ... private: int *data; int size; int cap;};Another way to do this is to use one pointer, finish, pointing to the next available space, and one pointer, end, pointing to pass-the-end of the array.

class vector{ public: ... private: int *data; int *finish; int *end;};There are some confusions why finish does not point to the last element, but to one-past it. The reason is that when appending a new element to the vector, you can directly assignment value to the space pointed by this pointer, and increase the pointer. This will reduce the code complexity and minimize the pointer-arithmetic operations. Another reason is that if you want to get the size of vector, it can be done by subtracting two pointers, finish - data.

Both approaches are valid. However, STD vector prefers the second approach to the first one. Therefore, I will use the second approach for the rest of the article.

#How growing works

#Push back

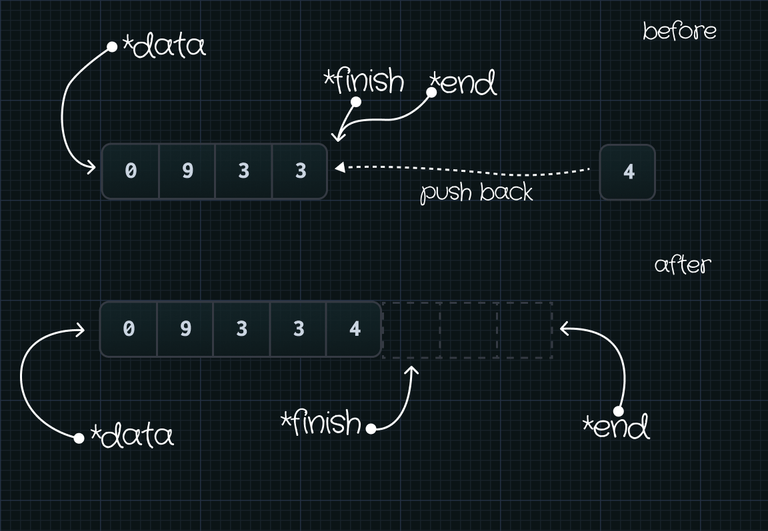

Let's consider the most used method in STD vector, vector<T>::push_back, which appends the new element to the back of the vector. The simple procedure to achieve this goal is described as below:

- Check if there is enough space (i.e.

end - finish > 0). - If there is enough space, go to step 6. Otherwise continue.

- Allocate a new space with a new, sufficient capacity.

- Copy the values from the old array to the new one.

- Free the space of the old array.

- Append the new element to end.

If our vector has enough space, the work to append a new element is simple; just assign it the space pointed by finish and increment the pointer. However, if there is not enough space, our vector has to find a new space. Allocation, copying and deallocation are expensive operations.

In terms of time complexity, if there is enough space, the time complexity . Otherwise, the time complexity to copy all data is , with is the number of elements. But since this happens once in a while,

push_backis said to have an amortized constant time.

To avoid allocating overhead, determining a new size is crucial. You can come up with crazy ideas to set a new size for your vector. However, a simple approach is to double the old size. In fact, this is how STD vector does it.

#Reserve space

At this point, we know that reallocation associated with vector is an expensive process, so we want to avoid it as much as possible. If we know how many elements we might need, we want to allocate that space beforehand.

STD C++ provides a method, called vector<T>::reserve() to achieve that goal. The method only increases the capacity when needed, and does not alternate the original elements.

vector<int> foo(8);auto print = [](const int& n) { std::cout << n << ' '; };

std::cout << "Old cap: " << foo.capacity() << "\n";

std::cout << "Data: [ "std::for_each(foo.begin(), foo.end(), print)std::cout << "]\n";

foo.reserve(100);std::cout << "New cap: " << foo.capacity() << "\n";

std::cout << "Data: [ "std::for_each(foo.begin(), foo.end(), print)std::cout << "]\n";Old cap: 8Data: [ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ]New cap: 100Data: [ 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ]#Insert new elements

push_back is a great method, and it solves almost 95% use cases of vector. However, there are certain scenarios that you might need to insert elements at somewhere else except at the back. This is where you might need vector<T>::insert().

#Without reallocation

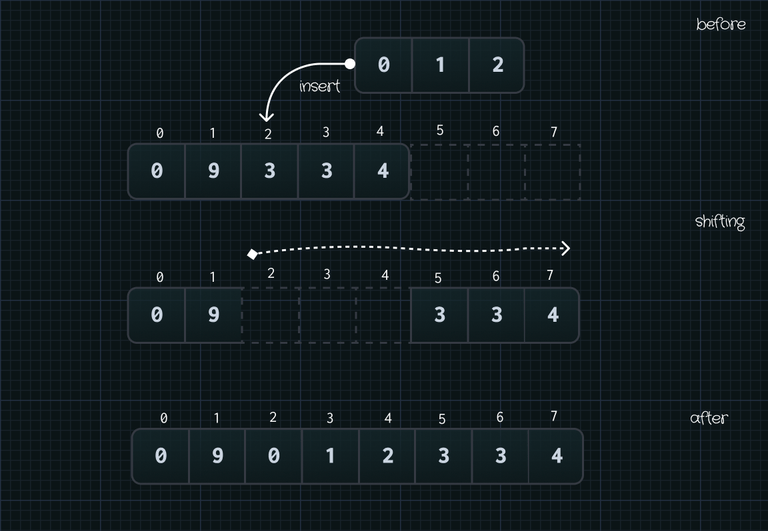

Since all elements in a vector are stored contiguously, which means there is no hole in a vector, inserting new elements at any random position requires some mechanisms to find space for new incoming elements.

That mechanism is called shifting. insert() will right-shift all the elements after the position to which you want to insert. After making some available space, you can now safely insert the new elements.

The shifting operation is the basis operation of this method, so the time complexity is linear depending the distance between your position to which you want to insert and the last element. In other words, inserting at the beginning of the vector is the worst case. Now, you get some ideas why vector is so great at inserting elements at the back but not at the front.

#With reallocation

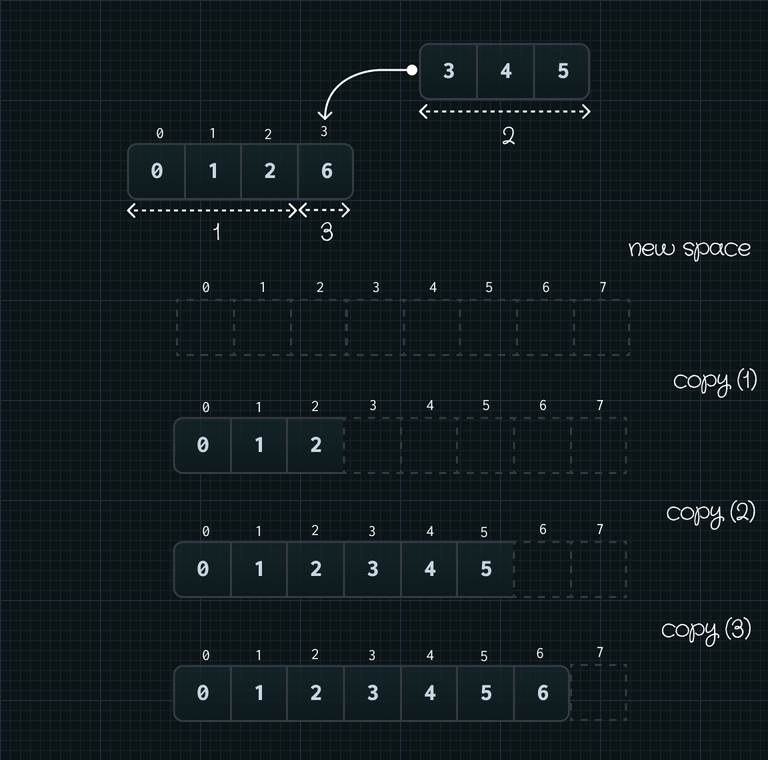

The idea is pretty same as what we discussed in How growing works. You need to find a space to store old and new elements. A simple approach can be as follow:

- Allocate a new array

- Copy the old array to the new one.

- Perform shifting and insert the new elements.

This approach is straight-forward, but there is a way to combine copying and inserting. We can split the copying process into 3 parts. First part is the elements before the inserting position, the second part is the inserting elements and the last part is the remaining elements in the old array.

This will remove the overlap between copying and shifting from the "naive" approach, and yield a better performance. This illustration might help clear things out for you:

#Conclusion

Vector is a wonderful solution to deal with fixed-size arrays. The actual implementation of C++ vector is way more complicated than what we have covered in this article. We have not talked about allocator, constructor, deletion, meta programming and iterators. Nevertheless, understanding the basis will help you understand how C++ works, and, more importantly, how reallocation works to accomodate new elements.

From there, you can try to recreate vector from scratch by yourself. If you're interested, you check my vector implementation.