The first time you learn about the C++ Standard Template Library (STL), you probably get confused by the term Iterator. STL uses iterators for almost operations. It provides access to the elements in the underlying container. But why can you not access the elements directly? What does it do?

Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, 1st EditionThe intent of an iterator is to provide a way to access the elements of an aggregate object sequentially without exposing its underlying representation.

#Introduction

C++ STL defines that an iterator is any object that, pointing to some element in a range of elements (such as an array or a container), has the ability to iterate through the elements of that range using a set of operators (with at least the increment (++) and dereference (*) operators).

In a nutshell, iterator is an interface that provides access to elements sequentially without exposing the underlying implementation of the object.

Let's say you have a binary tree. To traverse a tree, you can use any traversal techique that is your favorite. The problem with these traversing is that you can only traverse through the whole tree. What if you want to access the values in the tree one by one?

Iterators can help you achieve that goal. Instead of traversing the whole tree, iterator will give its users a chance to go one-by-one, or sequentially. And of course, you can traverse through the whole tree by combining a loop and iterators.

#Basic requirements

Each programming language has its own requirements on what basic methods an iterator must have. They can be defined under different literature. For C++, it's mostly defined as overloaded operators. For Python, it uses Data Model. For Java, iterators are inherited from the super Interface Iterable.

However there are certain functionalities that an iterator must support:

- Sequential iteration — iterators can be incremented to move to the next element.

- Termination — iterators should know whether there is any element left.

- Retrieval — iterators should be able to return the value of the element.

As mentioned, C++ supports these functionalities by overloading operators. For (1), C++ overloads the two unary incrementing operators, operator++() and operator++(int), to advance the iterator. For (2), C++ overloads the two comparison operators, operator==() and operator!=(), to support termination. Finally, you can dererference an iterator to retrieve some data with operator*() and operator->().

From now on, I will only focus on the C++ implementation of iterators.

#Categories

C++ supports a variety of iterators, depending on the need, the nature of the container and the underlying data structure to support that container.

From the basic requirements, C++ defines as the Input Iterator. That is the most basic iterator, which defines the basic functionalities of other iterator categories.

From here, C++ has other iterator categories according to different containers.

#Forward Iterator

Forward Iterator has everything that an Input iterator has. Additionally, foward iterators can be used as lvalue, which means its value can be reassigned.

An example to illustrate this point is by using the container std::forward_list. Forward list is a singly-linked list, which can be only iterated in a forwarding direction (from start to finish). That's the basic functionalities from the input iterator.

With forward iterators, it allows assigning new value to the element to which the iterator is pointing. This can be done by dereferencing an iterator via operator*().

#include <forward_list>#include <iostream>

int main(void) { std::forward_list<int> ist{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

for (auto curr = list.begin(); curr != list.end(); ++curr) std::cout << *curr << " "; std::cout << "\n";

auto first = list.begin(); auto second = ++first;

*second = -2; // Assign new value

for (auto curr = list.begin(); curr != list.end(); ++curr) std::cout << *curr << " "; std::cout << "\n";

return 0;}1 2 3 4 51 -2 3 4 5#Bidirectional iterator

Bidirectional iterator has everything that Forward Iterator supports. Additionally, it also supports decrementing operations, which means you can iterate from start to finish, and backward! As oppose to incrementing, which uses operator++, the decrementing can be done via two unary operations, operator--() and operator--(int).

Let's continue to illustrate this by using the container std::list. Unlike forward list, std::list is a doubly-linked list whose nodes have two pointers, one pointing to the next node and one pointing to the previous node. It can be iterated in a forwarding direction, just like forward iterator, and can be iterated backward too. And of course, bidirectional iterators also support reassignment.

#include <algorithm>#include <iostream>#include <list>

int main(void) { std::list<int> list{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}; auto print = [](const int &e) { std::cout << e << " "; };

std::for_each(list.begin(), list.end(), print); std::cout << "\n";

auto first = list.begin(); auto second = ++first;

*second = -2;

// Decrementing auto it = list.end(); while (it != list.begin()) { --it; print(*it); } std::cout << "\n";

return 0;}1 2 3 4 55 4 3 -2 1Now, iterating backward is troublesome since end() does not reference to the last element, but to one-past the last element. This accomodates the range [first, last). In C++ STL, if a container supports bidirectional iterator, it guarantees to provide rbegin() and rend() (prefix 'r' standing for reverse).

You can replace the decrementing loop with rbegin() and rend().

std::for_each(list.begin(), list.end(), print);std::cout << "\n";#Random Access Iterator

The final iterator category with the most supported operations is the Random Access Iterator. They can be used to access elements with an offset.

All the above iterators have one drawback when you look at the examples. If you want to advance an iterator to a certain position, you must repeat either operator++() or operator--() for incrementing and decrementing respectively. As a result, it also supports operator[] to directly access an element.

Random access iterators allow advancing iterators with an offset, which can be done by operator+(int) and operator-(int).

You might wonder "Why can I implement operator+(int) by repeating operator++() multiple times?". The answer is yes. However, it will takes a linear time, to complete the operation. The bigger the offset is, the worse it gets.

With random access iterators, the operation only takes constant time, , regardless how big the offset is.

An example of a container supporting this category is std::deque. A deque behaves like a vector, but it also supports operations at the front of the container with constant time too.

#include <algorithm>#include <deque>#include <iostream>

int main(void) { std::deque<int> deque{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}; auto print = [](const int &e) { std::cout << e << " "; };

std::for_each(deque.begin(), deque.end(), print); std::cout << "\n";

for (size_t i = 0; i < deque.size(); i += 2) print(*(deque.begin() + i)); std::cout << "\n";

for (size_t i = 1; i < deque.size(); i += 2) print(*(deque.begin() + i)); std::cout << "\n";

// direct access deque[5] = -6;

// advance by offset first += 3; *first = -4; first -= 3; *first = -1;

std::for_each(deque.rbegin(), deque.rend(), print); std::cout << "\n";

return 0;}1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101 3 5 7 92 4 6 8 1010 9 8 7 -6 5 -4 3 2 -1#Implementation

Despite having categories to define the expected operations, different containers have different implementation to accomodate their underlying representation. Some is very straight-forward, while some is complicated. Therefore, there is no universal implementation for all iterators.

For that reason, each container will define the implementation of its own iterator. This will include what type of traversal algorithm is, how the advancing works, how much the container wants to expose its underlying elements, etc.

Let's take vector and deque into comparison. Both support Random Access Iterator to access elements directly and advance iterators by offset. However, while vector iterators are just like pointers, deque iterators are way more complicated due to its map of nodes.

vector has an array as the underlying data structure. The container defines its iterator as __normal_iterator, which is basically a class wrapping a pointer. This iterator can perform any operation that a normal pointer can such as pointer-arithmetic operations, dereferencing, reassign, etc. Additionally, this iterator can support other utilitiies such as converting a const iterator to a normal iterator and vice versa.

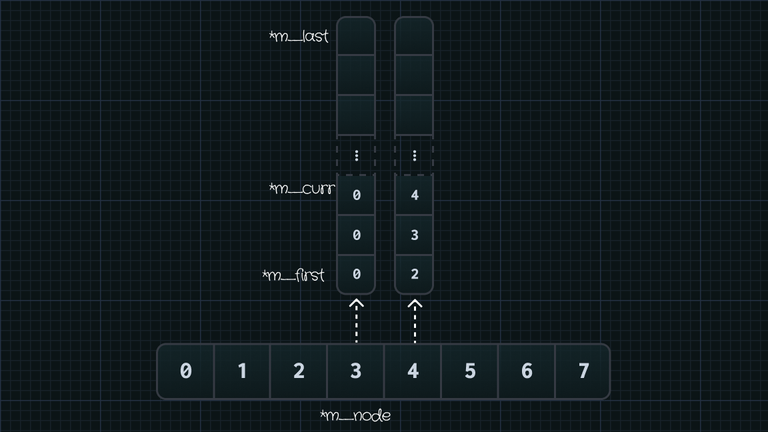

deque, on the hand, uses a map of lists under the hood. A map, in a nutshell, is an array whose elements are other arrays. Each iterator needs to know the pointer to the array, the boundary of the array and the pointer to the current element.

Most iterator implementations contain some essential information about the underlying data structure of the associating container. The information is usually represented in pointers. They will expose the location of the elements and their "surrounding environment" to the iterator implementation. Depending the traversal algorithm and the data structure, these information can be varied.

The iterator needs the information to cover all the possible scenarios that could happen when it performs the expected functionalities. For example, why deque iterator needs to know the pointer *m_node? Well, in case advancing the iterator moves *m_curr outside of the array, the iterator will advance *m_node and continue advancing with the remaining offset.

But thanks to the iterator, you don't need to know the detail of implementation when you use deque container. The iterator provides you an interface to access the elements sequentially without intimidating you with the complicated procedure.

#Conclusion

Iterator is a useful interface for programmers to access the underlying elements without worrying too much about the actual implementation. Unlike other programming languages, C++ publicly supports iterators in its containers. All STL containers need iterators to perform most of their methods.

Therefore, getting comfortable with iterators will help you work tremendously better with STL containers.