HTTP, the foundation of the World Wide Web, allows us to transfer data from one computer to another in a reliable way. But how does one know when the data transfer is complete? Can one send a sufficiently large object over an HTTP message? And if not, how can one break it down?

#Why bother?

HTTP, stands for Hyper Text Transfer Protocol, is a protocol built on top of TCP. TCP, in a nutshell, is a stream of bytes. For example, when a server wants send a message "Hello, World" to a client, TCP will send the message as a stream of bytes, like so:

server ---> 48 65 6c 6c 6f 2c 20 57 6f 72 6c 64 ---> clientThe client will then receive the message as a stream of bytes, and it will decode the bytes into a string, "Hello, World". But now, the client is asking itself: "Is that it?"

#Complete message?

There are many reasons to consider whether a received message is complete or not.

Old servers might have a fixed-sized buffer to send data. Many HTTP servers written in C use a stack-allocated array of some fixed size as a buffer to send data.

Modern servers might allow the buffer to store the whole data. But due to the nature of TCP, the server can only try its best to send as many bytes as possible1. The short answer is that TCP is a stream-oriented connection, which means the message is not guaranteed to be received as a whole. It might be received with the first line, 1KB of the content, or the whole message. The only guarantee is that the bytes will be received in the same order as they were sent.

#Special characters?

You might be asking.: "Can we just simply add newlines '\n' to the end of the message and stop reading when first encountering it?"

Well, what if the received message is just the first line of the whole message that the server wants to send? What if the server wants to send a message that contains newlines?

"Well then, we might use '\r\n' for the end of message while '\n' is for the newline characters".

That might be a good idea. But Windows uses \r\n as the official newline character, and certainly we don't want to discriminate Windows users, do we? Even that's something you want to do, which I highly discourage, HTTP messages use \r\n as the end of line character:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nHeader-1: value-1\r\nHeader-2: value-2\r\n<more-headers>\r\n<content>In fact, this is the standard for all Internet protocols2, not just for the HTTP protocol.

#Maybe we can inform the client?

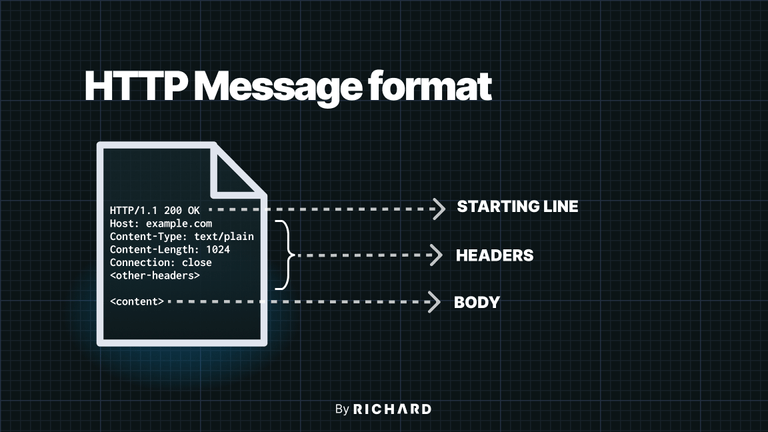

Luckily, HTTP provides a schema of messages so that client knows how to interpret the message.

The example above is a HTTP response message:

- The first line is the starting line, which contains the HTTP version, the status code, and the status message.

- The following lines are the headers, which contains the metadata of the message. To mark the end of the headers, follow a blank line.

- The rest of the message is the content.

Take a look at the Content-Length header. It tells the client how many bytes the content is. So, the client can read the content until it reaches the number of bytes specified in the Content-Length header.

#Content-Length Header

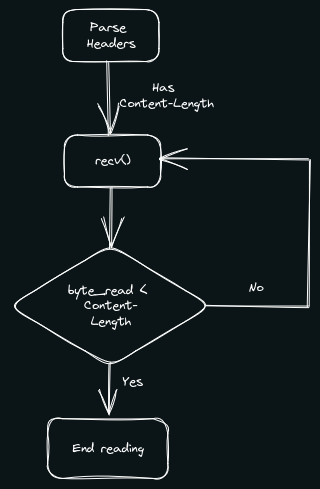

The purpose of the header Content-Length is to inform the client (mostly the user browsers) how many bytes the content contains exactly. Since TCP, as mentioned above, might send the message in multiple packets, the client must know when to stop reading the content and move on to other tasks.

#Implementation

To construct a response message with the Content-Length header, the server must know the size of the content beforehand. For static files such as HTML pages, the server can easily compute the value of the Content-Length header. Most programming languages provide a way to get the size of a file.

int fd = open("index.html", O_RDONLY); // Open static filesstruct stat st; // File metadatafstat(fd, &st);

// Response message templatechar *response = "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\n" "Content-Length: %ld\r\n" // Content-Length header "\r\n" "%s";

char *content = mmap(NULL, st.st_size, // Map file to memory PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, 0);

// Construct response messagechar *message = malloc(strlen(response) + st.st_size);sprintf(message, response, st.st_size, content);

// Send response message to clientssize_t sent = 0;<span class="mtk3 mtki"while (sent < strlen(message)) { ssize_t n = send(client_fd, message + sent, strlen(message) - sent, 0) if (n == -1) { perror("send"); exit(1); } sent += n;}

// Free resourcesunmap(content, st.st_size);free(message);close(fd);#Notes to consider

- If

Content-Lengthheader is present with a value, the receiving end only reads the content within the specified number of bytes.- If the content is less than the value of

Content-Lengthheader, the message is considered incomplete, and the receiving end will close the connection. - If the content is more than the value of

Content-Lengthheader, the receiving end will read the content until it reaches the value ofContent-Lengthheader, and the rest of the content will be discarded.

- If the content is less than the value of

- If

Content-Lengthheader is not present, the receiving end will read the content until it reaches the end of the connection.

RFC 7230 - Section 3.32 defines the Content-Length header more detailed.

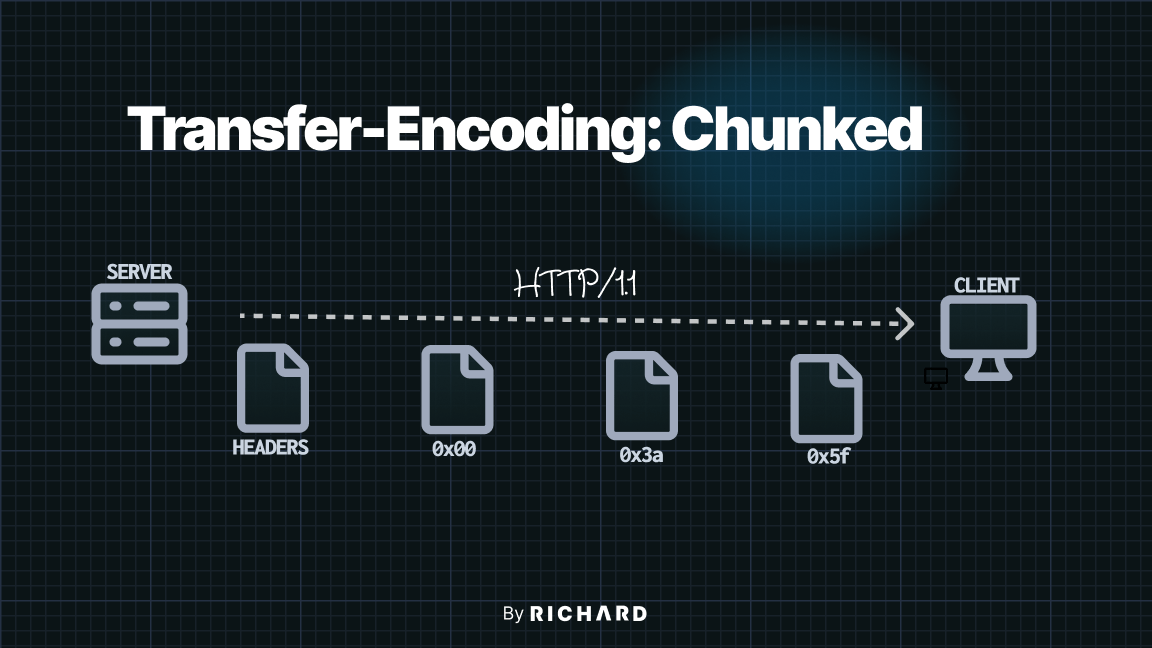

#Chunked Transfer Encoding

The Content-Length header is a great way to inform the client how many bytes the content is. But what if the server doesn't know the size of the content beforehand? What if the server wants to send a large file to the client? What if the server wants to send a stream of data to the client?

#Unknown content length

There are some situations where the sever cannot compute the size of the content before sending the response. It could be a video stream, or a result of SQL queries. In these cases, the server cannot use the Content-Length header to inform the client how many bytes the content is.

#Implementation

Like Content-Length header, the Transfer-Encoding header is used to inform the receiving end how to interpret the message, and when to stop reading the content. In HTTP messages, the Transfer-Encoding can be used as below:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nTransfer-Encoding: chunked\r\n...The tricky part is the content itself, or more specifically, the way the content is encoded. RFC 7230 - Section 4.1 defines the chunked transfer encoding as below:

chunked-body = *chunk last-chunk trailer-part CRLF

chunk = chunk-size [ chunk-ext ] CRLF chunk-data CRLFchunk-size = 1*HEXDIGlast-chunk = 1*("0") [ chunk-ext ] CRLF

chunk-data = 1*OCTET ; a sequence of chunk-size octetsNow, I admit, the definition above seems a bit confusing. However, we can break it down into smaller and simpler parts. Every chunked content has multiple chunks, (*chunk means multiple chunks), the last chunk and CRLF (\r\n).

Each chunk has 2 major parts: the size of a chunk and the chunk itself.

- The size of a chunk is a hexadecimal number followed by a

CRLFto determine the size of the chunk. - The chunk, or the content, is a sequence of bytes with the size specified in the previous step.

The last chunk, or the terminal chunk, is a specical in which there is no content. This last chunk is the signal to the receiving end that the message is complete.

#Example

Let's say we have a message looks like as below:

IT will be seen that this mere painstaking burrower andgrub -worm of a poor devil of a Sub -Sub appears to have gonethrough the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, pick-ing up whatever random allusions to whales he could anyways...The content can be arbitarily large and the server doesn't know the size of the content beforehand. We can only send the message line-by-line. Then, the chunked messages can be broken down into:

33\r\nIT will be seen that this mere painstaking burrower and\r\n3D\r\ngrub -worm of a poor devil of a Sub -Sub appears to have gone\r\n40\r\nthrough the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, pick-\r\n3C\r\ning up whatever random allusions to whales he could anyways\r\n...0\r\n\r\nWe treat each line as one chunk. For every chunk, we calculate the size of the chunk, followed by the chunk itself. The receiving end will read all the chunks and concatenate them into one message. Then, the last chunked message, 0\r\n\r\n, is the signal to the receiving end that the message is complete.

- HTTP requires the existence of the last chunk in order to determine the end of the message. If the last chunk is missing, the receiving end will either hang waiting for the last chunk if the connection is still alive, or it will yeild an error as incomplete message if the sending end has closed the connection.

- The receiving end might stop reading the content prematurely if the last chunk is present, even where the message is not complete.

#Which one?

#Content-Length

The rule of thumb when considering which header to use in your code is to use Content-Length header if you know the exact size of the content before sending.

Content-Length header has some advantages. First, it's simple to implement because you let TCP handle sending the content itself. Second, it only sends what it needs to send, as it doesn't ship extra bytes such as \r\n to accomodate the format of chunked encoding.

#Chunked Transfer Encoding

With that being said, there is only one reason to use Transfer-Encoding: chunked over Content-Length. If the content is large and the server doesn't know the size of the content beforehand. In this case, the server can send the content line-by-line, or chunk-by-chunk with fixed size. Thanks to the format

of chunked transfer encoding, the receiving end can read all the chunks and build them into one final message.

Footnotes

-

Beej's Guide to Network Programming 5.7. send() and recv() ↩

-

RFC 5322: Internet Message Format - Section 2.1 rfc5322#section-2.1 ↩